Mobilizations in the public space

Understanding Collective Action through experimental mobilizations in Bogotá, Colombia

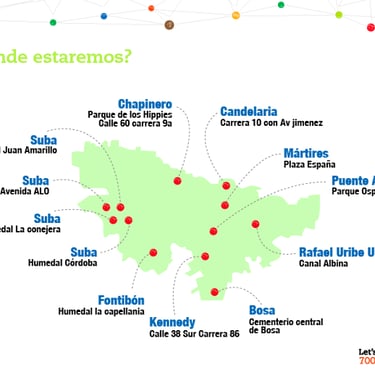

I co-founded a civic movement in Bogotá dedicated to promoting collective action and cooperation through shared experiences in public spaces. We designed and led large-scale mobilizations aimed at creating the conditions for people to collaborate and pursue common goals. Engaging directly with communities revealed the nuances of collective action at the micro level—insights often overlooked in theoretical approaches.

Questions like “Why should I stop littering if no one else does?”, “Does my small effort really matter?”, and “What’s the point of cleaning if it won’t stay clean?” were central to our motivation, particularly in addressing waste management issues in Bogotá. In response, a group of volunteers and I aimed to shift the narrative from isolated individual actions to sustained, visible contributions that inspire responsibility and encourage others to follow.

I grounded our mobilizations in principles from collective action theory, that provide useful guides to create appropiate scenarios for cooperation: designing the right incentives, crafting messages that connect to people, controlling the events to prevent opportunism, eliminating suspicion, providing correct and timely information, ensuring the security of the events and generating credibility.

These were needed as we were motivating citizens to wake up early on a Sunday morning to clean up Bogota's streets. Through practice, we learnt that the goal was larger: to prompt behaviors that demonstrate that lasting change emerges from our willingness to lead, influence others, and stay engaged.

This is what we learned by intentionally linking theory and practice:

Micro intentions reveal the true essence of altruistic behaviours

In scenarios of collective action, it’s often the small, spontaneous gestures that reveal the true nature of altruism. These micro-intentions—subtle, genuine acts driven by personal values—may not be recognized in theory as catalysts for collaboration, yet in practice, they proved essential to the project's success.

We observed people correcting one another, sharing knowledge, demonstrating skills, smiling, and simply coexisting. These seemingly minor actions had a profound effect: they didn’t follow a script, but instead reflected authentic engagement. Rather than large-scale conformity, it was these organic, human interactions that sparked the deeper sociological framework of the project.

These micro-intentions became a foundation for the next phases of our design. We prioritized and encouraged any form of interaction that fostered cooperation—however small—knowing that real collective behavior often begins in these quiet, meaningful exchanges.